For Eastern NC, the “list” of well-adapted clumping bamboos seems to be limited to cultivars within Bambusa multiplex. Otherwise, most clumping species are either poorly adapted to our potential winter temperatures, or unable to handle our summer heat. When planting non-native bamboos into the landscape, it’s critical that we do choose clumpers and avoid the runners due to the extreme invasiveness that has been observed with non-native running species (for example, see the NC Forest Service note on Phyllostachys aurea). In our part of the state, we do have a native, running bamboo, which is variously described as Arundinaria gigantea; Arundinaria gigantea and a smaller related species, A. tecta; or A. tecta as a variety of A. gigantea. It’s certainly worth conserving for its wildlife value, but doesn’t seem to generate much interest as a cultivated landscape plant.

A clump of Bambusa multiplex ‘Silver Stripe’ was planted at the Craven County Agricultural Building around 1995. It has performed well, but does take a beating in the colder winters. Currently there’s a need for a major cleaning out of dead stems, many of them left over from the winter of 2018. Additional pruning is needed to reduce the number of stems that have sprawled out, virtually sideways, from the otherwise well-behaved clump.

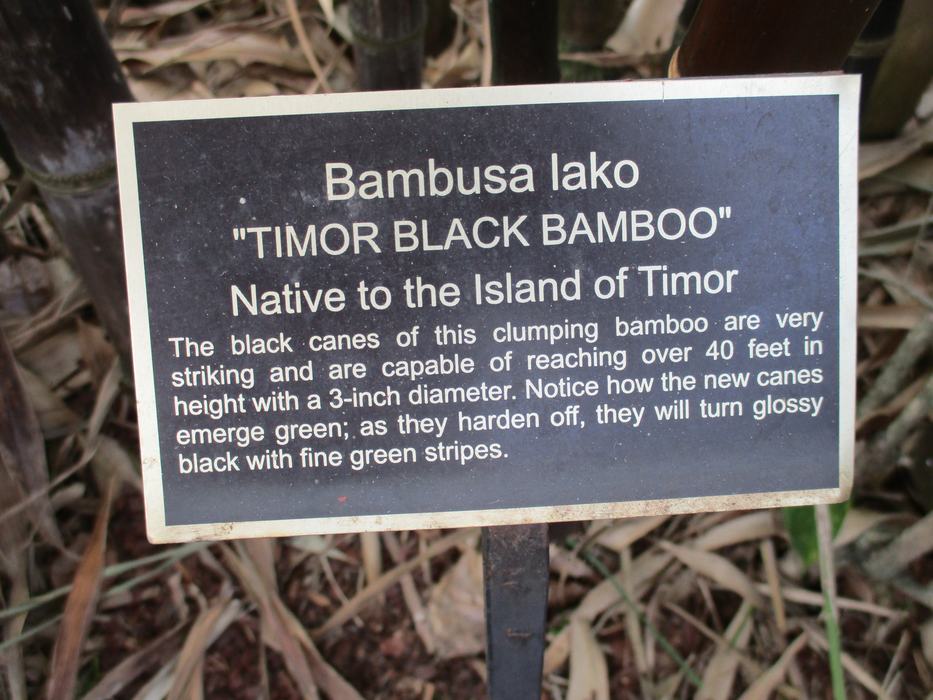

The clumping Bambusa lako (Timor Black Bamboo), recently spotted at Disney World’s Epcot Center in Orlando, would be a great complement to our B. multiplex planting, but the cold tolerance just isn’t there. (Interestingly, B. lako nomenclature is under discussion, and the plant may end up placed in a different genus.)

It’s easy to understand the attraction of non-native bamboos, but the great majority that can survive here also happen to be aggressive, running types. Many of these individual infestations run on for about as far as the eye can see, causing great harm to native plant communities.

For additional information, see the March 2019 publication Growing Bamboo for Commercial Purposes in the Southeastern U.S.: FAQs.